Ten to Ace. June 19, 1942. Winnipeg Tribune.

by Bob Gates

As you know, the history blog has a soft spot for the early days of racing in the “Peg.” The horses, people and events associated with River, Whittier and Polo Parks, along with memories from Assiniboia Downs in its formative years, provide an abundance of material for our stories. While the history may not always be familiar to us, these stories are treasures of the past that are worth telling, and tell them we will!

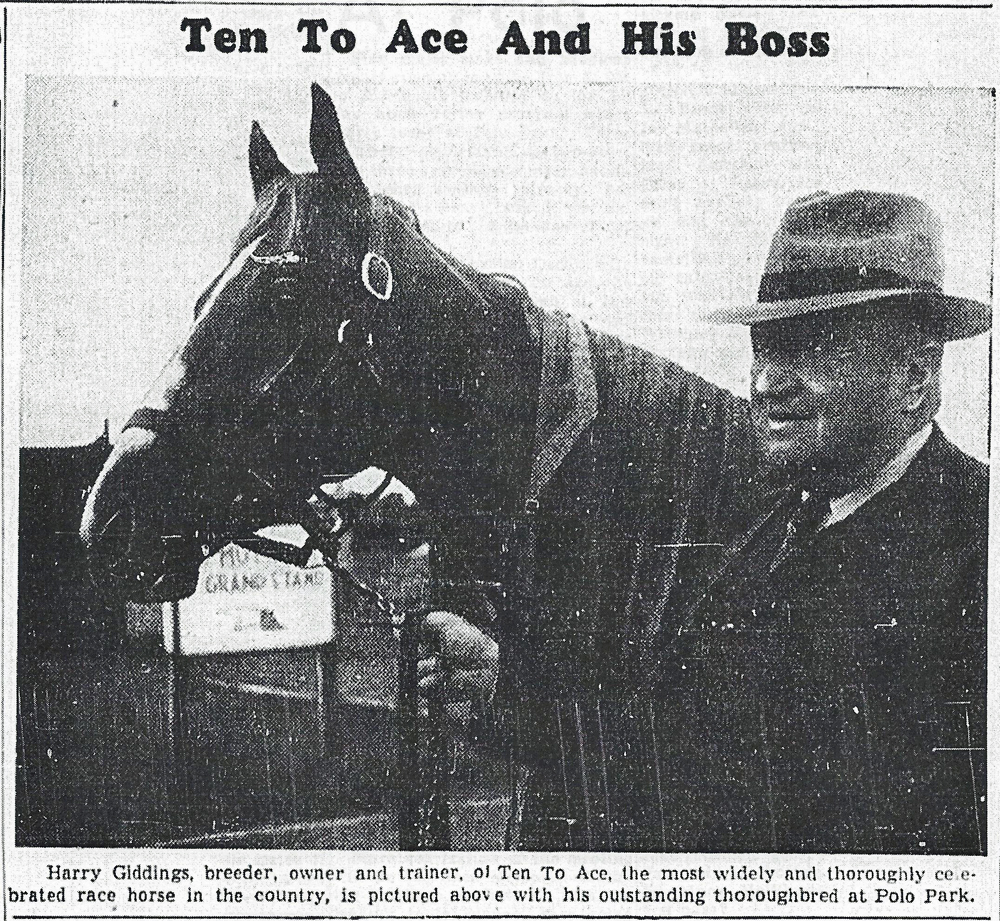

Most of you will not recognize the name Ten to Ace, nor are you likely to have heard of his owner, trainer and breeder Harry Giddings. Some might recognize the groom’s name, Ted Mann, but even that is doubtful.

Groom Ted Mann went on to become a notable trainer down east. Ted scored two wins in our Manitoba Derby. He won the 1964 and 1966 editions of the Derby with Langcrest and Carodana. After Langcrest’s Derby win, Ted was asked about Ten to Ace, even though the horse had been off the racetrack for almost 25 years. As he was getting ready to board his plane to head home to Toronto he offered:

“My thanks to the good citizens of Winnipeg for their hospitality.” Then he shrugged as he added: “The heck of it is, that there weren’t 20 people in the grandstand today who remember Ten to Ace.”

Our mission here is to preserve memories and there’s a good case to be made that the older the story, the greater the reason to keep it alive. So, who was Ten to Ace and what is his story?

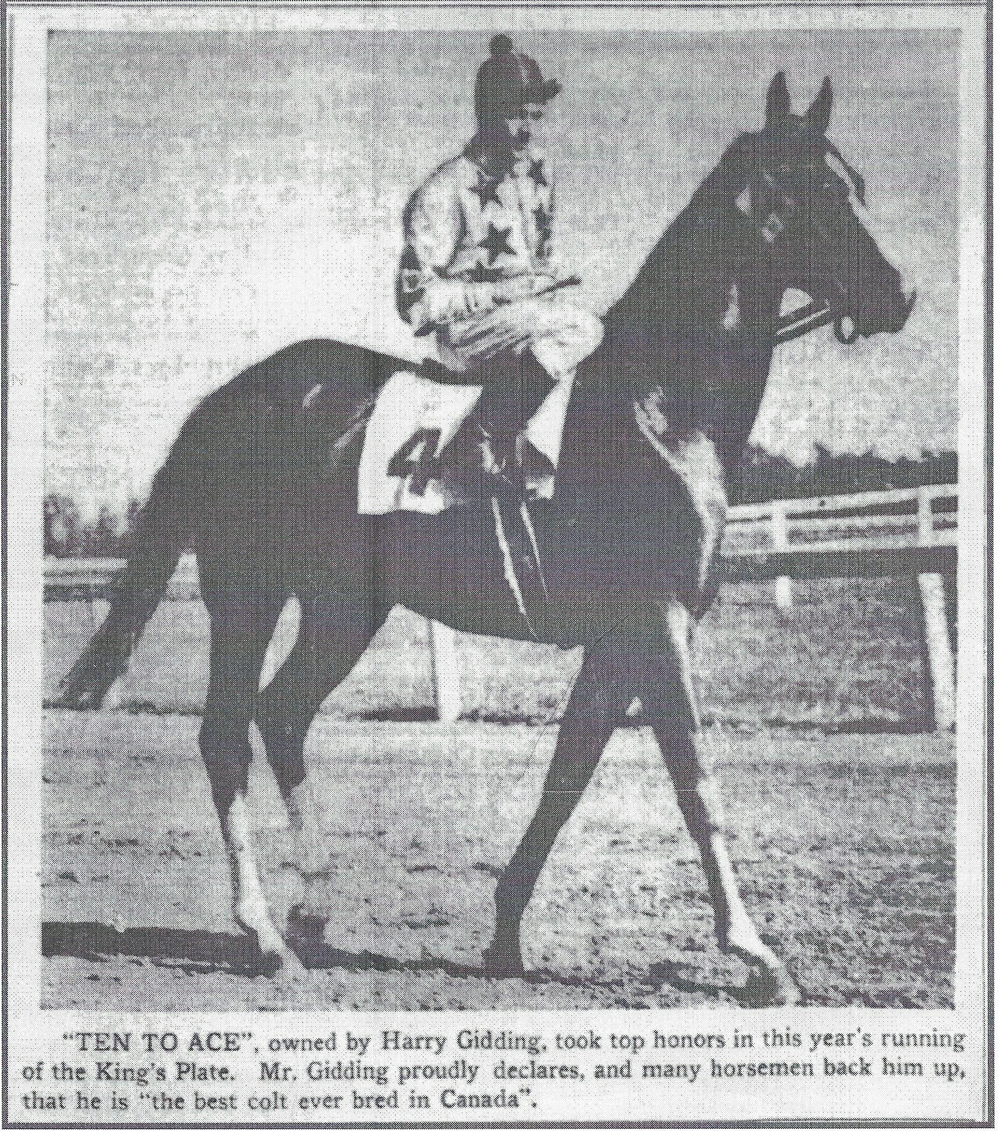

Ten to Ace won the King’s Plate in 1942 and without a word of exaggeration was the recipient of many accolades. He was ranked as the greatest thoroughbred ever raised in the “Dominion.” He didn’t just beat his competition, he routinely tow-roped fields. Some spoke of him in the same breath as Man O’ War.

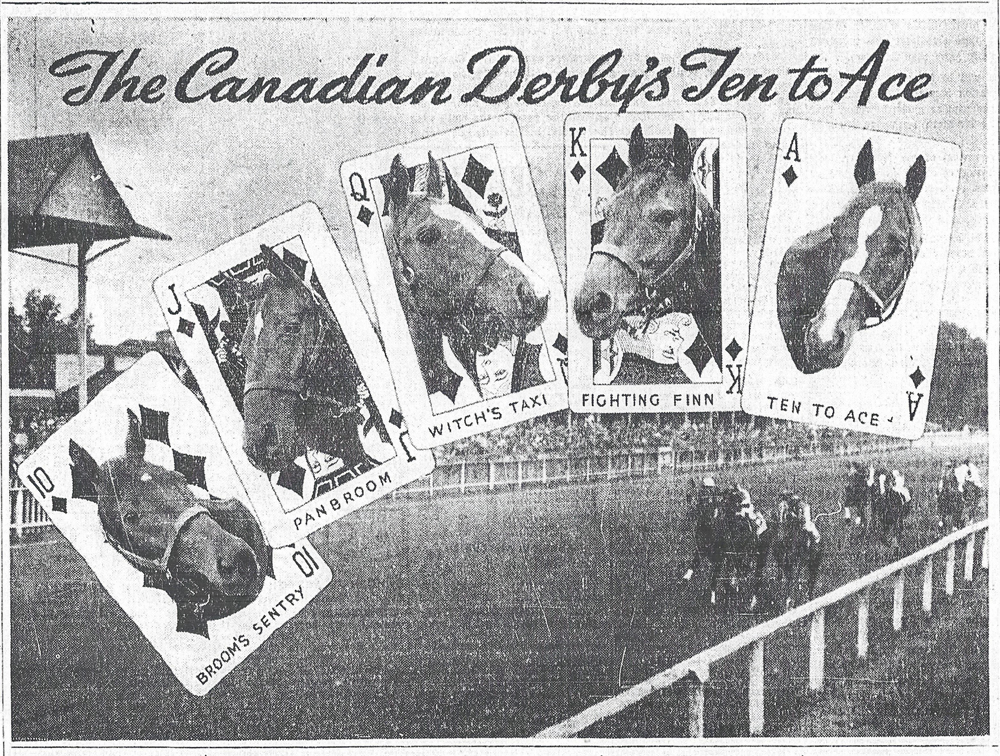

Speaking of the 1942 Canadian Derby “They’re apt to measure the margin of his victory in furlongs.” Print media of the 1940s described Ten to Ace as “One of those horses which comes along once in a generation” and declared him to be “The greatest Canadian-bred of all time.”

Harry Giddings was from Oakville, Ontario and trained no fewer than eight King’s Plate winners, mind you they all pre-dated 1942. This feat ranks Mr. Giddings with the best trainers in the history of Canadian racing.

Giddings had a promising 2-year-old in 1941 who was making quite a name for himself. Ten to Ace was his name and as a yearling he worked three-furlongs in :33 4/5. Aptly named, the Giddings colt was by Stand Pat out of Royalite. He was indeed a royal flush of a colt, whose workout was reported to be the fastest that Canada had seen in many years.

Ten to Ace led the parade of 2-year-olds in 1941 with earnings of $10,730. The white-faced chestnut won six of his seven starts and was widely reported as the fastest Canadian-bred the nation had seen. His only loss came when he got hung-up in the gate, injuring a leg but still managed to finish a fast-closing third.

In the spring of 1942 Ten to Ace was the leading eligible for May’s King’s Plate, as well as July’s Canadian Derby. He would have been entered in the Kentucky Derby were it not for the King’s Plate eligibility conditions.

At that time, horses entered in the Plate were forbidden to race outside of Ontario before fulfilling their Plate commitment. Yes, he had to pass on the Kentucky Derby for his shot at Ontario’s King’s Plate. In addition, the field of 3-year-olds were all Ontario breds who had not won a race in 1942, as per the conditions of the Plate. It was a different time, wasn’t it?

The outcome of the 83rd Running of the $8,000-added King’s Plate on May 23, 1942, was a surprise to no one. Ten to Ace won as he pleased and made the competition look like a bunch of plough ponies. Local print media put it this way:

“There is no racing term which adequately describes Ten to Ace, he may have courage, but he didn’t have to use it, he may be capable of a closing drive as impressive as his early foot, but he didn’t need that either. The truth is simple: He can just run faster than any other 3-year-old in Ontario.”

After the Plate it was evident that Ace was everything they said and more! On June 4 the Plate champion added the Prince of Wales Stakes to his already glowing resume.

Manitoba Derby 1966. Caradana. Second from left, Ted Mann, second from right Duke Campbell.

The Ten to Ace train was steaming along at full speed with plans to tackle the best runners in the United States, but first there was a whistle stop at Polo Park for the July 1 “Dominion Day” Canadian Derby.

The 1942 running was only the second year for the race known as the Canadian Derby (open to all Canadian breds), but it was actually the Derby’s 13th running when you factor in the 11 previous Manitoba Derby races (open only to horses bred in western Canada).

Racing pundits were hard-pressed to find any serious contenders from the proposed Derby field. The pre-race hype had reached a fever pitch. The consensus was that local racing boss Robert James Speers would save everyone a lot of trouble if he just mailed Giddings a cheque for the $5,000 purse. Toronto sports columnist Jim Coleman summarized it this way:

“Ten to Ace won’t lose at Winnipeg unless some exasperated Western gambler shoots the Giddings’ colt before he crosses the finishing line.”

Even though confidences were high, there were dark clouds on the horizon. First there were reports of “liver trouble,” then a “shipping fever” but neither were seen as a serious impediment to Ten to Ace’s ultimate victory in the July 1 Derby. Ten days prior to race, newspapers reported that Giddings was confident his horse had fully recovered.

Ten to Ace. 1942 Winnipeg Free Press.

In the lead-up to the Derby the decision was made not to sell mutuels on the race. For the most part the decision related to the fact that Ten to Ace was an incredible prohibitive favourite. In addition, the Derby races of 1937 and 1939 had also been “no betting” contests, so the recent precedents smoothed the way for a “no wagering” race.

As you’ve all probably figured out by now, Ten to Ace laid the biggest egg in his Derby run. The form chart read:

“Ten to Ace opened a long lead with fine speed. He held on well for a mile and then gave way suddenly, finishing a tired colt.”

The star of Giddings’ stable was running as though he was his old self. He had opened a huge lead which was described as any where from 12 to 25 lengths when he “hit the wall.”

According to the American association of Equine Practitioners:

“A horse inhales and exhales once every stride. At .42 seconds per stride it completes 2½ breathing cycles a second. At full gallop, the horse takes in five gallons of air a second. From that air it extracts one quart of oxygen through its lungs, transmitting that energy-fuel through its bloodstream.”

Around the mile-marker Ten to Ace is reported to have shown signs of distress. “He began to shorten his stride and the lengths of daylight between the easterner and the westerners began to shorten and within a sixteenth of a mile Ten to Ace was a beaten colt and it wasn’t long before …his proud head was down around his knees.” Ten to Ace’s flow of oxygen had slowed to a trickle. He was done. Sadly, the colt had literally been choked by his own speed.

One of the greatest turf upsets of all-time was witnessed by a crowd of more than 15,000 patrons at Polo Park racetrack. Following his defeat the rumor mill took flight. First, they said the horse had died, then that he never won another race and that he never raced again. All of which were not true.

Annually for the next 30 years or so a discussion about the Canadian Derby always included the mention of the “fabled flop” of Ten to Ace. Even his name fanned the flames of what became the legend of the Canadian Derby of ‘42 – the day a royal flush was a losing hand.

The Canadian Derby’s Ten to Ace. Winnipeg Tribune. 1942.

As “recently” as 1986 his disastrous run still made the sports pages. So why are we talking about it today? Because nothing this historic should ever be lost to the sands of time. It is an important part of Manitoban and Canadian horse racing history.

Meanwhile in that place where time stands still, there is a multiple stakes-winning chestnut son of Stand Pat grazing in a lush green meadow. All these years later, there he stands in that pasture of “Eternal Youth” where horses are rewarded with their forever home.

His afternoon feeding interrupted, he raises his head, flicks his ears and anxiously swishes his tail. He knows that someone, somewhere, is talking about “that race.” Ten to Ace is visibly annoyed at our remembrance of the 1942 Derby.

In a fanciful way you can hear him snort “Good grief! Give it a rest, that was more than 80 years ago. I wasn’t myself. I was sick and ran a bad race. I certainly didn’t die as a result of that Derby. I continued to race and racked up more wins before I retired to stud. I thought that nightmare was long since dead. How about we leave it be! I’ve more than paid for that day. Haven’t I?”

Let’s borrow a line from the old police television series the “Naked City” that aired from 1958 to 1963. Each episode ended with the narrator saying…

“There are eight million stories in the naked city. This has been one of them.”